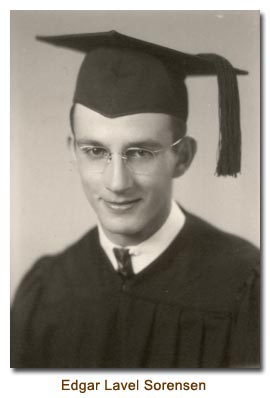

Edgar Lavel Sorensen

I was born November 26, 1918, in Mendon, Cache County, Utah. I had two brothers, Owen and Eldon, and two sisters, Veda and Hazel.

The youngest time I remember is the time when I was trying to ride a little pony we had. I wasn’t old enough to ride, and I wasn’t allowed to, but one day I had coaxed the pony up to the feed manger with some oats and while she was up there I crawled on her. I wasn’t big enough to get the bridle on her, so I just crawled on her and I rode her out the door and went up the lane with no bridle. Of course, my mother got real excited because I wasn’t old enough to be riding. She had no way of catching the horse and getting it back to the barn. That was my initiation into riding.

Even before age six I was already taking the cows and horses to the pasture every day. That required that I get up about 5 a.m. and go down to the pasture below town in the dark. The pasture happened to be right by the railroad tracks where the bums would always come in and spend the night. So, I was always terrified when I got down to the pasture gate. I would sit up where I could rapidly open the gate and get the horses out and get home. It was a terrifying experience for me because I had been sharing a room with my older brother, Owen. I idolized him, but every evening when we were going to sleep he would tell me stories about the bums and about the boogieman that he said was up in the attic of our house. There was a big hole in the closet ceiling and he would scare me to death every night while I was going to sleep. So, that was part of the problem with going down to get the horses.

I shared a bedroom with Owen until he got married. We always had an excellent relationship. Our whole family had a good relationship. When Owen left, Eldon started sharing the bedroom with me.

We never had a furnace, just a coal stove. It was about as cold inside as it was outside. In the mornings, it could be thirty below. Dad would get up first and start making the fire. But we still had to jump into ice-cold clothes and go down to take care of the cows. Milk the cows, feed the cows, and take care of the horses. Then we would come back for breakfast, which always was one of the biggest meals of the day. We always had cereal first, then bacon and eggs, fruit, and always potatoes. We had potatoes three times a day. We had cooked cereal. We could never afford cold cereal. It was ground wheat that was cooked.

The coal stove in the kitchen was used for cooking. There was a stove in the dining room for heating. It burned wood we would cut up. We would go up to the mountains and drag down wood, then cut it up with the saw. But the bedrooms were all cold. There was no heat at all in the bedrooms. We kept those doors closed so that we could heat the dining room. We never even opened the living room. It was kept closed except when we had a party or something. The living room was never furnished until a few years before mother died.

We had an old lantern we would hang down in the barn to milk with. We never had electric lights in the barn.

On Easter Sunday, we always went to Church in the morning then in the afternoon the kids went up to the mountains to have a cookout. It was always ham. We lived largely on pork. We always slaughtered a couple of pigs each year. We would have a couple of slices of ham and some marshmallows and would take some potatoes and put them right in the fire. That would give them a flavor you don’t get with the tin foil. The potatoes would get a charcoal crust.

We would go up into the mountains by the creek and have a fire. Practically the whole town would be up there one time or another. We would always pick wild flowers and take a bouquet of these back to our parents.

At the time I lived on the farm, we didn’t have tractors. Everything was done with horses. The plow was a two-bottom plow with six horses. It would take about an hour to get the horses ready to go in the morning. Then it would take another hour to feed the horses at noon. Then it would take another hour at night to take the harness off. We never really had any tractor equipment at all at that time. It was all horse-drawn. To get the hay up in the barn we had one of those forks that would hook into the hay, then we would have a horse on the other end and he would pull the hay from the hay rack up into the barn and drag it across. That’s the way we filled the barn with hay. The hay was all pitched on the wagon by hand. There were no hay loaders. We raked the hay with a horse rake into piles. Then it would all be pitched onto the wagons. This was prior to the time of any mechanization on the farm.

I was recognized as one of the best riders in the town. On May Day, which is one of the big celebrations of the year, we would have horse races and potato races. We had a bucket of potatoes and you would take a potato and jump on the horse and ride down a couple of hundred yards, then drop the potato off, and go back and get another one. It got to the place where no one would race me anymore. So we didn’t have any more races. I got to the place where I could stand and ride the horse standing up. At the same time I could use a lariat and catch the back leg of a cow while he was walking and I was standing. I got real good with a lariat, but I never had a saddle. Dad could never afford a saddle, so we would ride bareback and when I would catch a cow, I’d lose my rope because I couldn’t hold it. Eventually, Owen did get a saddle.

We always had at least a couple of cow dogs. One was a cattle dog and one was a Shepard dog. The Shepard dog would go every day with me to get the cows and all I had to do was to hold him high enough so he could see over the hills and see the cows, then he would go out and bring the cows in. I’d usually be up on the horse or on one of the high hills and he would go out and circle the cows and bring them back in.

In the pasture in the springtime, we were close enough to the river that when the river flooded it would bring a lot of the fish up into the pasture. When the water went down, the fish would get trapped in the ponds and we would go down with pitchforks and spear the fish. We would get sacks of fish. We would grind them up so they would be like tuna fish. We’d also shoot them with .22 caliber rifles. It was hard to shoot them under the water. You’d always misgauge it.

I think that everyone who grows up on a farm learns responsibility very early. Before I was six years old I had responsibility for feeding the pigs and feeding the chickens. We always had about ten head of calves I had to take water to. At an early age, you learned discipline and responsibility. You learned the consequences if you miss feeding for a day and how important it is that when you agree to do something, you do it. You also learn the need for each other. On a farm you really depend on your family and you are dependent on each other. The whole community is dependent. It becomes a large family. For instance, my brother got sick one year and was in the hospital. The whole community turned out and topped his ten acres of sugar beets. When a person gets sick, he doesn’t lose a second because the whole community is there to help out. It’s the type of thing where you are almost brothers and sisters in a small farming community. You are always helping each other.

I spent a lot of time working for my uncle. He had a machine called a binder. At that time, when the wheat was cut, they had a machine that came along and cut it and wrapped a string around it, tying it into bundles. My uncle was the only one who had this machine. My dad was always in debt to him because he cut our wheat for us. So, I spent my life helping my uncle to pay off the bill for binding our wheat. I never did get any money from it, so I somewhat resented it. I did all sorts of work for him. When I did get paid, I got 10 cents a day. Later he raised it up to seventy-five cents a day. That was the most I ever got for a ten hour day. That’s when I was a teenager.

To make what little spending money I had I would take cows for Elmer Hancock and he paid me forty cents a week. I started picking up other people’s cows until it got to the place where I was bringing up about two hundred head of dairy cows each evening and distributing them to various people along the road. That got to be quite a thing when you start sorting out those cows at each person’s place. When you come to their place and you drop off their cows, you have to make sure everyone has their cows. This got to be quite a job in itself.

That was basically the type of employment we had as youngsters. I had a cousin who I thinned beets for. We got $7 to thin an acre of beets. It would take about two days to thin an acre of beets. We were making about $3.50 a day thinning sugar beets. I also worked on the thresher. I was what they called the water monkey for the thresher crew. A steam engine powered the wheat thresher and I had to haul the water for the steam engine. If I was a little bit late, they would start tooting away on the steam engine’s whistle that they were about out of water and that I had better come quick. The engine burned coal and we had to keep the coal supplied to the engine.

I remember one day for May Day we had the May Queen, and the May Queen had her maids, and one of the maids selected me as an escort. I had saved up twenty-five cents and that’s what we could spend on that May Day. That meant we could get some ice cream cones. The ice cream cones were about a nickel. You could get a bottle of pop for a nickel and that was about the size of our date – an ice cream cone and a bottle of pop. Then we would go to the dance in the evening, which was a treat for us. That’s about the type of spending money we had.

I was always very attached to my mother. We had a close relationship and I grew accustomed to her being there when I came home from school. I started school at age six. Mother was always there when I came home from school. She always had something there for me to eat. The thing I really liked was cinnamon rolls. I guess I had so many then that I don’t care too much for them now, but I was always waiting for those cinnamon rolls, or whatever she had waiting for me, before I had to get on the horse and go to the field.

I always thought a lot of my mother. She had to have the kindling wood brought in to build the fire the next day. I tried to keep the buckets full of coal and I tried to do everything that I could to please her. She always did so many things for me. We were essentially the doctors in the family. Dad didn’t like to doctor animals. He pretended to be busy when anything got sick, so it was always mother and me that had to do the doctoring. One of the mares had a little colt and it was sick and couldn’t get up and dad said, “Well, if you want to take care of it, you can have it.” I got mother and we gave it an enema and I held it up while it nursed and it got better. Then before I went in the Army the horse was big enough to break and work.

Dad was a true Danish farmer. He did not know how to play. He got his satisfaction out of working from dawn until dusk. He never relaxed that I would know about. He always put in a hard day’s work and at the end of the day when he would be sitting down at night, he would study for his Sunday school class. He would spend every night getting ready for Sunday school. He was a very quiet person. Dad and I never had any problems. We always got along well. The only time he would relax would be on the Fourth of July. We would always go over to Logan on the Fourth. They had a parade over there and they had all the concessions and a horse show and a dairy show. This one-day of the year was dad’s only splurge.

On Saturday afternoons, though, dad and mother would go to shop. Their half a day off was to go to Logan and get the supplies for the next week. The supplies in Mendon were very expensive. So, he did take Saturday afternoon off, but he didn’t let us take it off. So, we kind of had to make up for him taking it off.

I remember that our first car was a 1927 Dodge. Prior to that, I remember driving over to Logan. It used to take a half a day to get over there to go to the dentist or something, in an old buggy, even in the middle of winter. Mother would heat up some old bricks and put them in the bottom of the sleigh and we would put our feet on those and we’d be all bundled up. We’d tie the horses up to an old tie rack. It wasn’t until I was in my teens that we had a car. I did get to drive the old 1927 Dodge. I went all through high school without driving. That was a time in my life when I was interested in girls and would have liked very much to drive a car.

We had a lot fun with the girls. We had what we called the galloping goose. It was old electric train that ran from Mendon up to Hyrum where the South Cache High School was. We had to ride the old train up there. We would meet our girls up at the dance and then they would take the train and go their way home and we would go our way.

I never really got to drive a car until I went to the university. I never knew I needed glasses until I went to get my driver’s license and they told me I couldn’t see. Then I found out that was why I was always sitting on the front row in the classrooms. I got my glasses and everything went fine. When I graduated from the university and started doing graduate work I got a research assistance ship, which paid me $50 per month. My sister was also working in Logan teaching school, and my other sister was working, so we all contributed and we bought a 1940 Plymouth, which cost about $900. Dad paid about $300 and we paid the rest on it. So that was the first car I really drove much. I drove the old ’27 Dodge around Mendon a little bit.

My father was a musician. He played the baritone in the band. He was the choir conductor for twenty-five years. One day he brought home a new trombone and said, “you’re going to start playing the trombone.” So, I took the trombone in high school and oddly enough I became first chair. (They had a very poor trombone section!) I guess the part I enjoyed about it was that the band would always go around to all the celebrations. Someone would have an onion day and someone a peach day and so the band was always in demand and we would go to the fairs. Actually I was always a shy type of person and the bandleader asked me on several occasions if I would be the drum major. He thought I would be a good drum major. He tried to get me to lead the band on several occasions, but I never wanted to do that.

High school was really the time that girls were in my life, because when I went to the University I went four years through school and never had a date. But, we were really involved with the girls in high school. I had a girlfriend who, oddly enough, people thought we were going to get married because we were together almost constantly through high school. I never had any particular feeling for her. Looking back on it, I wonder why we ever did that. We were at the place where everyone was saying we should get married. She would embarrass me by putting me up as a candidate for president of student body, which I didn’t like.

We used to have a band in Mendon– some of our relatives had a band that was known all over the valley. Every Saturday they would have a dance in Mendon or Hyrum. Dancing was a very popular pastime. We even went over the mountain on Saturday where they had a dance in connection with a swimming pool. You could go swimming. We had a lot of swimming parties because they had a pool in Logan. Dancing was the main form of entertainment.

The only movie my father ever went to was a religious show. In his whole lifetime, he never went to a show. But they did have one religious show. That was the only show he ever went to.

I don’t remember either of my grandfathers. Grandfather Sorensen I remember very vividly in his casket. I didn’t really want to see him in his casket, but my parents made me go. That’s probably why I remember it so vividly.

Grandfather Ladle was killed very early in life. He fell off a load of hay just a half a block from where we lived and he died. I do remember him vaguely.

I remember both my grandmothers very well. I was very attached to them. Grandmother Sorensen was a real Danish lady and she always made barley beer. My mother would never go down to visit her with dad, but dad would always take me– I don’t know why, but I was the only one out of the five kids dad would take. But mother was so frightened that grandma was going to give me a drink of this barley beer that she would threaten dad that if he ever allowed it, that would be the last time.

I used to go down to visit her and she had these little squares of sugar that she used to sweeten her tea with. I really liked those. Every time I went down I got some of those, so I knew if I went to visit her I’d get a little square of sugar. I would go down and sit on her steps and she knew I wasn’t going to go until I got that square of sugar.

I remember my grandmother Ladle very well. She outlived most of her children. She had eleven or twelve children. Every Sunday they would come up to her house to visit. The whole family would come and have a big time. There must have been 30-40 grandchildren, so it was a big occasion. She was always real nice to the grandchildren. When she was old, Madall and I would take money up to her because she never had any money. Instead of giving her presents we would give her money. She always took such good care of her children and grandchildren.

I remember when my mother died. She had a stroke and I was down in Provo. They called me long distance. I came back home and we were sitting with her that night. She only lived a couple of days after that. I remember grandmother Ladle sitting there and she said, “Your mother is going to die tonight, she won’t be here in the morning.” And she wasn’t. She died that night. She had that understanding that she knew when this was going to happen.

The depression didn’t really have any impact on me. I was born in it. I never had anything and never expected anything so it didn’t really have that much effect on us. We always had plenty to eat— mainly pork and potatoes. We didn’t have things like toothpaste. I never had toothpaste until I was out on my own. We always brushed our teeth with salt or soda. We didn’t have much, but we didn’t miss it. It wouldn’t be like going from having things like we do now, and then trying to get by on a little. If you’re born with just a little, you grow up that way and I think you have just as much fun as kids as if you had a lot of money, because no one has anything. I think you’re just as happy as if you have a lot of things. You didn’t have clothes. You wore your clothes until they dropped off. Everybody did. We didn’t notice it. We always had plenty to eat. Many people did lose their farms during that period. Dad was able to hold on to his.

After high school I went to Utah State University. My brother Owen was very mechanically minded and could do anything mechanically. I wasn’t that way. With my allergies, I hated working the hay and with the thresher because I couldn’t breath. I decided the farm wasn’t for me and I was going to do something else. The reason I got in Agronomy was because I knew more about agriculture than anything else. Not because I should have done. I probably would have been better off in business. But I did that because that’s what I knew. We didn’t really know what was available to us as students. All we knew was what our parents did.

I started in agronomy and did well enough. I minored in chemistry. I stayed on as a graduate research assistant after I graduated and I started my master’s degree. I had all my research laid out at the time I was drafted into the Army. I essentially wasted a year of my life because I got everything set up, but I wasn’t able to collect my data. I graduated in 1941 and I should have gone directly into the Army, but my sister was on the draft board. They were deciding who went in who didn’t. The University was pretty hard pressed for people to stay there and work on research because everyone was going in the Army, so they asked me to ask for a deferment and I got it. Then all the people in the town blamed my sister saying that she got me off and I didn’t have to go war and everyone else did. The pressure got to the point that I finally quit and went into the Army. That kind of terminated my graduate work. After being in the Army three years and coming back, I went to work instead of going back to graduate school.

The army was regimented to the place where a person really learned discipline. They tell you when to get up in the morning, when to comb your hair, when to brush your teeth, inspect your rifles, and when to go to bed. Then when you got overseas, over to New Guinea, the situation was a little bit different. The officers were a little afraid of what someone might do to them, so life was a little better once you got into the combat area.

We had some good experiences in New Guinea. Getting acquainted with the life of the Fuzzy Wuzzies and how they lived was interesting. We watched the kids that were three years old run up a coconut tree that was 30-40 feet high and pick off a coconut. The families always marched in groups. The father was at the head of the line, then the kids, then the mother at the back of the line. They lived in little villages.

We had a lot of experiences. The Japs’ were there in the mountains right behind us. They would stay up in the mountains until they would about starve to death, then they would come straggling into camp. We had a bunch of them there that we were guarding all the time. When you were on guard duty, that was quite a feeling because the Fuzzy Wuzzies could be on either side. They were on the side of the people that they thought were going to help them at the moment. They could slip up behind you when you were out there on guard and they had their arm around your neck and you wouldn’t even know they were there until you felt that arm around you. It was quite a frightening experience.

I remember the first time we went to an invasion of a little town there. The tanks were supposed to be giving us protection from the enemy, but we got so far away from them and were on the wrong side of the tanks. We didn’t really know where they were.

We actually, at the time we landed in New Guinea, landed in those little landing crafts. We came over on the USS Mount Vernon, which was a monster, and they could only come in so far. Then they had these little landing barges that would take you in. We had our first bombing raid when we were getting unloaded from those things. They bring you in to where the water was just above your knees and you would wade into shore. We were just in the process of heading in and the bombers came over. When we moved up to the Philippines we lived in a coconut grove.

We were trained as anti-aircraft artillery. We were supposed to go into the African invasion and we had all the equipment and were ready to ship. Then we got the measles and we were held up and not able to go. Our group was supposed to detect the sound of enemy planes as they approached using a sound detector. Then, we would alert the search units and they would throw the lights on the plane and that would blind the pilot, then our planes could come in from the back. Later on they got radar, which was much better, so we were really a radar unit. But the radar was really more of a defense type of thing and by the time we got there we were on the offense. We had trained for months on how to live in the dessert, and then we went to Florida and learned how to live in the swamps. Then we were shipped to New Guinea and over there we never did use our radar outfits. We were attached to the Air Force for a long time. That was the best time I was there because the Air Force has the best food there is. But then we changed to unloading the ships so for a long time we were attached to the quartermaster and we would unload all the ships that came in. They were little freighters that would go up the coast of New Guinea. We got caught in a cemetery thing one time where we were digging up a graveyard and transferring people from one graveyard to another. So, we were attached to all sorts of outfits and they used us wherever they needed us.

I learned to play ping-pong in the military. That was one of the pastimes. We had competitions between battalions, so it got to be quite a competition. There were a lot of people coming in to watch.

I was in the military just over three years. I got a stripe on my uniform with one stripe for three years. The war was over in 1945. I was home by 1946. We had been over there longer than any other outfit, so we were among the first to come home. We were all ready to go in for the Japanese invasion when they dropped the A-bomb, and that ended the war. We were supposed to have furloughs to Australia every six months. But we never had one, so we had been there a couple of years with no furlough from the front. That meant we were one of the first units to come home. We came home on an old Navy ship, which was so slow it took about a month to get home. We went over on Christmas and we were on the seas coming back on Christmas. We got back in January.

When I came back I decided that I would take a job with the Bureau of Reclamation for a year. Then the state asked me if I would be the state seed supervisor. When they changed governors, they dropped us all. Then I got a job with Production and Marketing for a couple of years after that. The last day that we could sign up for the GI bill, I decided to go to graduate school to get something better. I never would have gone back to school if I hadn’t had that deadline staring at me. I went back to graduate school at Utah State University. Going back to school was quite frustrating because I had been away for ten years. Within the first month we had to take an exam on every course they offered, whether we had taken it or not. That was a perquisite for getting into the school. I had been there for a year before, so this was going on for the second year to get a master’s degree. It was no fun for mother or me, since I was working night and day. Then, we went from there to the University of Wisconsin. I spent three and a half years there getting my doctor’s degree. I actually spent about nine years from high school getting the doctor’s, which is much longer that most people would take. A lot of this was due to changing schools. The new schools require things that force some duplication. That’s a long time to finish the degree.

I chose the University of Wisconsin because a Mormon was the head of the Agronomy Department and he had written down to Utah State to see if there was anyone there who might be interested in going to graduate school. I was graduating at that time, so I agreed to go up. It was in the area I wanted to go into. I started my research work on Alfalfa before the war. After I came back, I worked on barley, and I finished my masters on barley, but I was really interested in forage crops. Wisconsin was considered one of the best forage schools in the U.S. So it was a good opportunity to go to the forage school.

I first met Madall when we were going to high school. I was a senior and she was a freshman. She was down on the third chair group of trombones and I was up on the first chair. We sort of made eyes at each other, I guess, because we ended up making little bets with pieces of candy. I made bets on things I knew she would win before I bet her. We had that little thing going for the last year I was there. We used to have the dances there every Saturday and Madall would come to these dances, but she’d always come with her parents and some girlfriends. The girls would dance all night together. I would get my courage up, that when this dance was over, I was going to go up and ask her to dance, but before I could get over there, they would disappear in the powder room. After the dance, I was going to ask her if I could take her home, but her parents were there and that kind of scared me off. So, nothing ever happened.

Going through the University I never came in contact with her. I actually never dated anyone at the University, except Brother ElRay Christiansen’s daughter who worked there. She come up one day and got me engaged in conversation to find out if I was a Mormon. I quoted her the Articles of Faith. It never occurred to me that she was trying to strike up an acquaintance. There was another girl on the second floor of the building where I worked that would invite me up there for grape juice. Her boss would have people in and treat them, and after that she would invite me up to have grape juice. I would wait down there on the second floor for my ride home. Eventually, it got to the point that she would bring her typewriter down and she would type there while I was waiting for my ride. But, I still didn’t catch on to what she was working on.

Mom and I never really dated until the time I got out of the army. The whole time I was in the army I was writing to another girl in my hometown. When I got out of the army, I got a job with the Bureau of Reclamation for a year, then I quit that, and I was offered the job as a state seed supervisor. That job was in Salt Lake in the state capital. Mother was working there also. It was just natural that we started playing tennis. Her and another girl had an apartment there. I would go up and eat with them most of the time. I was traveling all the time, so I’d bring back peaches and apricots and tomatoes. That was my contribution to the meals!

That was how we got together. We were only engaged a few months before we got married. The thing that precipitated our marriage was that Madall’s parents were living in Salt Lake for the winter. They were going back home in the spring and we could take over their apartment. So, if we were going to get married, then why not now! The apartment was a Church apartment and Mom’s father knew the church people well enough that he could get the apartment, so he actually kept it in his name for quite a long time and we paid him. That was a pretty nice place to live. It was right across the street from the temple. We knew that we would get along all right. We had the same ideas. We were ready.

We got married in the Logan Temple in 1948. We came up to Mendon. We had quite a large group at her home. They were coming through there for hours. We went over to the Logan Temple. That was the time my mother was having high blood pressure and she couldn’t go. But my father went. ElRay Christiansen married us. It was a nice ceremony. We were quite surprised when we came out, because we were older – I was about 29 when we got married – we got outside and my brother and some of his friend had really painted up the car. We didn’t really expect anyone would do that type of thing for someone our age.

When we got through that night, it was so late, that we decided to sleep right there in my folks home. My brother and all his pals were waiting there to parade us out of town. They were waiting there most of the night and no one came out! They were really disappointed! We had a lot of fun.

I worked another two years in Salt Lake for the Production Marketing Association. The farmers could sell excess potatoes or wheat to the government. I was involved in that and in writing up conservation programs for the farmers, and this sort of thing, for a couple of years. Then, it got to be the last few days that we could use our GI bill and I decided I was going back to school. We went up to Logan for a year to get my master’s degree in barley. I graduated in 1952 and received my MS in Agriculture. We went from there to the University of Wisconsin. We spent three years there in a grass-breeding program. Bryan was well on the way when we left Utah and he came along shortly thereafter.

I was just getting started in school and we found out Bryan had to come Cesarean. Mom had gone in the hospital the night before, but they sent her home and we had to pay for all the x-rays because they didn’t keep her over night. She went back in and the baby came about 1 a.m. in the morning. It had to come cesarean. Mom just barely got out of the operating room and the doctor said the baby was fine and mom was all right and so while she was still in the emergency room, I went to class, and then after class I came back and visited with her a few minutes. Then I had to go back to school the rest of the day. That was a frightening experience. She was all hooked up with tubes because she couldn’t be fed through the mouth. That got to be quite a period until we got things squared away. We were trying to get started in school, and were having a lot of problems at the same time.

We weren’t really concerned about whether it was a boy or a girl. We had talked about names for a boy and names for a girl. We had quite a time with Madall’s father because he was so set that the boy should be named Todd. I’m not sure why Todd, but he had a fix on the name Todd. We couldn’t talk him out of it. He was real upset that we didn’t name Bryan as Todd. We liked the name Madison. One of my professors was named Madison and I liked him as an individual, so that was how we ended up with the name.

I guess it was a real satisfying for me to have a son. Bryan was three years old by time we left. By the age of three, Bryan was out in the swimming area at the lake every day. I was coming out of the hot sorghum fields and so going swimming was the first thing I wanted to do too. We would go over there almost every night and get in the water.

We enjoyed Bryan very much. At the age of three, he was a real runner. I had a difficult time catching him. Mother couldn’t! He always wanted to run away. The only way we could get him to come back was to get in the car and drive off! When he saw us going down the street, he would come running back, but at that time, he could run fast enough that I could just barely catch him!

We never had car seats in those days. Bryan would not sit down in the seat. He would always stand. He would stand for hours with his arm around my neck, and I really got a kick out of that. At the age of three he was really working that steering wheel. He was just captivated by automobiles and the mechanics would say that kid has almost cranked that wheel off the shaft! He would sit on my lap when he got a little bigger and he would drive the car. When he was just four or five years old, he was driving the car! I really enjoyed Bryan while I was at Madison those three years. It was pretty tough going through school. A number of the couples that we knew separated before they got through because the wife just refused to go through that type of a situation where the man was completely taken away to something else. I think that we might have taken that same track if Bryan hadn’t been there to hold us together. You spent night and day on your project and a lot of couples never made it through. The wives just said I’m not going to stand for that sort of thing.

When I graduated with my PhD in 1955, there were no jobs. We hadn’t been home for three years. We had stayed right at Madison for three years, so we decided to go home after I graduated. We thought maybe when I got back something would open up. By the time we got back, there was a whole raft of jobs. There was one down in Alabama on forage crops. There was one in North Carolina, which was the only good school in the south. There was one at Texas A&M and one at New Mexico, and one at Arizona. I talked to my major professor and he said Kansas was really the best school out of the group. The southern schools weren’t much yet. The job at Kansas State University was in alfalfa. I liked alfalfa, even though it is a difficult crop to work with.

It was real nice the way it worked out. We were real depressed when we got out of school because there was just nothing there. When we came back, there were all these jobs available at once. We took the job in Kansas largely because it was working with alfalfa, plus my professor’s encouragement that Kansas Sate was the best school that was offering jobs at that time.

It was discouraging when we first got down here. We found out that the fellow who preceded me had retired before I got here and had a graduate student working on the project – just maintaining it. I only had $400 left in the project when I got down here and that was in November. I had to go clear through the next year on that money. Mother came over as my research assistant and we worked together the first year. It was quite a struggle and the project really wasn’t well funded for several years. It was hard to make much progress when you had to do all the little things. You would have some student help, but they never learned how to help you out much. It took quite a few years to get the backing from the state and the federal government— to show them we had a program that should be funded.

There were many years in there when we didn’t really make a lot of advancement. Then, there was a period of years when the money came in and I got the support of the experiment station director, who funded about everything I wanted, and I thought we did pretty well from then on. I started out being secretary of the central alfalfa conference, and then I got to the chairman of the conference. Later, I was selected as project leader of the north central states. Then I was selected as chairman of the national alfalfa conference. After that, I was selected to be on the national certified alfalfa variety review board. There are only four people selected for that group. That’s considered a prestigious job for our area. I was also selected for chairman of the crop registration committee for the American Society of Agronomy, so I feel like I’ve done very well for our profession. Still, I’ve got a lot of things yet to do. Everyone would like to leave some lasting impression. I’m hoping some things will materialize that people would remember you by, so I’m not quite ready to retire yet. I’m hoping I can hang on until some of these things materialize that people would remember you for.

Since I started the first year, I’ve been working on resistance to the various things that plague the crop here in the southern Great Plains. When I arrived, that was the year that the spotted alfalfa aphid arrived in Kansas. The first thing we did was to develop a resistance to that and we did this within less than four years after the aphid arrived. We selected the plants, evaluated them and yield tested them and got a variety on the market. My major professor was quite happy with that. Following that success we decided we would tackle the pea aphid. No one had been able to come up with a resistant variety prior to that. We developed Kanza, which had resistance to the pea aphid and the spotted aphid and to bacterial wilt. The bacterial wilt threatened the existence of the crop in Kansas. Then gradually more money became available and we were able to expand into a number of different areas. We have now developed a resistance in one germ plasm pool to seven different pests. That has not been done in any other crop. No one else has done it in alfalfa. It’s quite a task. It’s easy to develop resistance to one thing, and when you think that they’ve had all the way from seven to nine pathologists and breeders in wheat working for over 30 years on resistance to rust, and they still don’t have it, it’s quite an accomplishment to develop resistance to seven pests.

Following Kanza, we released Riley alfalfa, which had a number of these things in itself. Riley had resistance to several pests and diseases. Riley has been very well accepted. In fact, I was quite surprised this fall when the breeder from Nebraska, who has developed varieties for Nebraska, came down here for breeder seed of Riley, because Riley was performing better in Nebraska than anything they had developed up there! Then, of course, I mentioned the work we did on the glandular hairs. No one had ever been able to cross a perennial and an annual – alfalfa is actually a perennial – and the annual has the glandular hairs. For years, people have been trying to make the cross, and just this past year, we were able to make the first successful cross. It looks like we are going to be able to utilize this germ plasm in alfalfa.

Richard was very capable as a student. He was a good mathematician. I think he could have gotten into mathematics or computers very easily.

I think all three of the kids had a period to go with me to the greenhouse and help me take care of the plants on Saturdays and Sundays. Rick and Janet would go over with me and they had all these games they would play in the trees over there while I was working.

Janet was more daring. She just scared the devil out of me. She would crawl clear up to the top of the trees and I’d go out there and there she was way up there on a limb bending back and forth in the trees and I’d try to coax her down so she wouldn’t break the limb. She was just a real wiry thing. They had their tree houses over there and they mapped the whole area and they’d bring their map home and decide what they were going to do. So, they had a good association.

We had a good association with all our children and I’ve mentioned this to my high priests because they’ve had so much trouble with their children. I’d say, I don’t understand why, because I don’t understand what I’ve done to deserve it. I could come in when Bryan was busy upstairs. Busy studying or something. I’d noticed that we have a leak up here on the roof and we needed to repair it. I’d ask, “Could you come out and repair it?” I’d put Bryan up on the roof and I wouldn’t dare get up. But anything I ever asked any of my children to do, they always did it. Willingly did it. They could have been antagonized because they were very much involved in another project. So, I always appreciated that. I’ve watched where Rick and Janet know those things that make me happy and I can see them doing those things and trying to do it unknowing to me. I don’t have any priority on this couch, for instance, but when I come into the room, everyone vacates that couch! Then know the things that I like and they are always going out of their way to do those things for me.

We always felt very fortunate that our children never got like other teenagers where they rebelled against us. They never rebelled against us and I felt like we always had a real good relationship with each other. We tried to help them. We tried to make no unreasonable demands. And in turn, they would help us. Anytime we asked, anything, they were there. I think it’s going to stay that way.

Janet’s always been special to all of us. All of us enjoyed having a young lady in our lives. She was kind of carried around on a platter. Her every desire was met. I felt the same way as the two boys did. We really catered to her. We all enjoyed Janet very much. Very early, she demonstrated her interest in art. Way back in the first grade, the teacher started recognizing her art. She’s never swerved from that. I continually keep telling her, how are you going to make a living when you get through because there’s no money in art? But that has not changed her mind. I think it’s good that she’s going on regardless to do what she wants to do. And I think that she’ll find a way to make a living. I’ve always tried to steer her away from it because she’s very talented. She wasn’t particularly good in math. She had to work hard to get it, but she always got A’s and she could have done something like that. She could have got into science or something else. But why do it if you don’t like it? We’ve been proud of her. She’s really been dedicated to go to the University. She made up her mind she was going to do it in three years and she didn’t care a lot about recreation. She went to summer school and intersession and she did it and she got through, and now she’s going to Iowa and I think she’ll follow through the same way there. She’ll go up there and do a good job and when she gets through, something will come along if she wants it. She’s been very special to all of us, mother included. I don’t know of any mother and daughter that have been as close. They had endless conversations and they are so close that it makes you feel good. Most daughters when they go through their teenage years, they depart from their mother and have fights. We never had that. So, we felt good about that.

I mentioned earlier that I pretty much devoted my young life to my uncle, paying off the debts that my father owed to him. He was the Bishop and he got quite attached to me. He took over the deacons and he made me president of the deacon’s quorum for the years I was in there. He did teach us a lot. He taught us the books of the Old Testament and the books of the New Testament. He told us if you want to know how many books there are in the New Testament, there are three letters in New and nine letters in Testament, and 3 times 9 is 27. There are 27 books in the New Testament. There are three letters in Old and nine letters in Testament, and if you put 3 and 9 together, there are 39 books in the Old Testament. I always remembered it that way. He taught us to recite the books of the Old Testament and the books of the New Testament, and he taught us all the scriptures that we needed to know as a missionary. I never really used those, but I remember them, like Ephesians 4:5 – one Lord, one faith one baptism, John 14:2 – in my father’s house are many mansions, John 14:6 – I am the way, the truth, and the light. All those things that I’ve never really used much I still remember. He had us recite them and recite them. And then, I went to the teacher’s quorum and wasn’t involved in the presidency. I got to the priests and I got involved again. That was the teenage years when most of them were off drinking and carousing. It got to the place where me and another guy were blessing the sacrament every Sunday for the three or four years that we were involved in the priest’s quorum Week after week and year after year we were up there blessing the sacrament because most of the rest of the group were renegades. On those Saturday night dances I talked to you about, they always had a member of the Bishopric down there to smell people as they come in to see whether they had been drinking or not. One Sunday I asked one of the priests if he would bless the sacrament with me and we got up there all ready to bless it and the Bishop came down and said “This fellow won’t be able to bless the Sacrament today.” I about fell under the bench because somebody had decided he had been drinking the night before and he wasn’t worthy to bless the sacrament. I had to tell the guy that he couldn’t bless the Sacrament.

I was ordained an Elder in 1938. But at the time I was ordained an Elder, they decided I should be the leader for the deacons and I spent two or three years as an instructor for the deacons. Then I went into the army. When I got to Manhattan they made me Superintendent of the Sunday school. I did that for about fifteen years. Then I quit and was immediately put in as high priest group leader and I’ve been in there ever since.

I was also treasurer of Bluemont PTA, and institutional representative for the Boy Scouts. I was institutional representative for the Church and on the scout committee. I was also treasurer for the Stake Welfare Farm.

The year that Janet was born, we started construction of the church building in Manhattan. We started digging the baptismal font. I got stuck with that, which was quite a job. The soil was like brick. It was a real dry summer. You would have to take a crow bar and chip the soil out. Took forever to dig that thing. We just built a little structure. We did all the work it still cost $65,000. The church sent a contractor out who was very lenient with us. He taught us how to do the whole thing. He worked along with us. We laid all the brick and did the roofing. We had a fellow from Wichita come up who was a member of the church and he helped put the tar on the roof, but we did all the painting and ceiling tile and the whole bit. It still amazed us how much it cost. From there we added on the junior Sunday school wing, then after we added on the chapel and later the recreation hall.

I can’t remember the name of the apostle, but he said it’s not possible to make more than you can spend. No matter how much you make you can always spend more that you can make. The basic thing you have to learn is that no matter what your salary is, spend less than you earn. Learn to separate wants and needs. I want this, but do I need it or can I get along without it for a while. The person who is unable to do this, is unable to manage his money, no matter what he makes, he’s always going to be in trouble.

We never did have a formal budget in our house, but we did learn how to manage money so that we didn’t spend all that we made. A budget is something a lot of people need and can follow. I had a friend that said that the only way he could save money was to purchase something like a house and he had to make payments and that forced him to save. Whenever he got his check, the check was gone unless he had something that he had to pay. So that was the way that he forced himself to save.

If we didn’t know this was the true church, we would never have stayed with it as many years as we have.

![]()