Mendon, Spring of 1859

Robert and Alexander Hill, who were among the early settlers at Wellsville, or Maughan’s Fort, in 1857, were attracted by the streams of water west of where Mendon is now located. They located some claims and constructed a dugout on the bank of Deep Canyon Creek in the north part of the present settlement. Their principal headquarters, however, were with the people at Wellsville.

The next year, 1858, a general 'move south' was ordered because of the coming of Johnson’s Army and the few settlers at Wellsville, the Hills included, temporally left the Valley. In the summer of that year, however, Alexander Hill with a number of others, returned to the Valley and harvested the volunteer crop of grain and they got about twenty bushels to the acre. Through the advice of President Brigham Young, the resettlement of the Valley did not commence until the spring of 1859.

In May 1859, Alexander Hill, his sons, Alexander, James, and William, Rodger Luckham, Robert Sweeten, James G. Willie, Charles Shumway and families; Charles Atkins, Alfred Atkins and families; Isaac Sorensen, Peter Sorensen and Peter Larsen decided to locate where Mendon is situated. The soil appeared to be deep and rich and there was a good water supply for irrigation and culinary purposes. Mr. Henry Hughes was also among the party but he did not locate here at this time as he decided to look elsewhere for a place. He assisted in surveying the site for the fort in August of that year and also helped to cut hay in the river bottoms. He did not settle permanently in Mendon until 1862.

As the planting season was pretty well along when the settlers arrived, they commenced at once to make wooden beams for the plows; also to make their triangle harrows with wooden teeth. The land had to be broken up and it was hard work, especially for the ox teams as they were so poor and weak. It became necessary to cooperate and help each other by putting two or four yoke of oxen on the plow and breaking land one day for one man, and then another day for another man, and so on, until each had a piece of land plowed. Each then used his own team to harrow the land and put in the crop, as this work was not so heavy.

The country around the little settlement then known as the North Settlement, being north of Wellsville, was strikingly beautiful. Everywhere from the Muddy River (Little Bear River) to the mountains was like one green carpet of rich waving grass and it was not long until the oxen became fat and lively as wild cattle. After the crop was put in, the Indians became rather threatening and Peter Maughan advised the settlers to make Wellsville their headquarters where they could get better protection. Accordingly, all the families were moved to Wellsville where it was intended to build their houses. The men went to and from Mendon to look after and irrigate the crops. Due to the dry condition of the soil and the lack of rain some of the grain did not sprout and it became necessary to irrigate it.

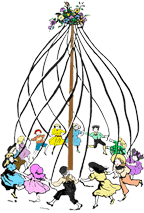

On the 24th of July, all the settlers gathered at Wellsville for a celebration and a big feast. They had many pies made from the rich juicy mountain berries and plenty of good fat beef and other good things to eat. At the second table, many Indians were fed and they took part in the celebration. After the feast the settlers enjoyed themselves in a dance under the bowery on a dirt floor.

In August of 1859 the settlers at Mendon began to make some improvements and the fort was surveyed and laid out in lots for building. The plan was to build two rows of log houses facing each other with a six–rod street between, extending north and south. There were roads around the sides and ends of the Fort. Each lot was eight rods wide and to the rear of these was a street for convenience to enter at the back of the houses and also to enter corrals and stack yards on the opposite side of this street. Beyond the stack yards, or hayricks, were the gardens, which made up the outer parts of the fort.

As winter approached, the settlers turned their attention to building their houses. The Hill's and Sorensen's were the first to complete their log house in the fort. All the houses had dirt roofs and dirt floors.

The grain that fall was harvested in September and the last of it in October, and some of it was frosted. A chaff–piler came from Brigham City and did the threshing, but it was necessary to haul the grain to Brigham City to get it made into flour. About twenty-five bushels to the acre were harvested this year. This fall the Findlay and Foster families, Ira Ames, Gibson and Winslow Farr, Charles Bird, John Richards, Andrew Andersen and families arrived.

At first only a temporary organization affected in the settlement with Charles Shumway, Sr. in charge, but in the fall of 1859 the ward was organized with Andrew P. Shumway as the first bishop. Just how and why the name “Mendon” was given to the settlement is not known. The private houses were used for holding the public meetings.

Early in the winter of 1860, it was decided to build a combination school and meeting house. The logs for the building were secured in the mountains west of the settlement and were slid down what is now known as the Slide. The snow was so deep that some of the men were hitched to a log and dragged it through the snow to break a trail. The logs were then hauled to Edward’s Sawmill, where the next spring Millville was located, and sawed into lumber for the flooring with an upright saw. More logs were obtained in the Millville Canyon and it was not long until the building was ready for the roof. In the spring a dirt roof was put on as there were not any shingles to be had in the Valley and it was too expensive to purchase them at Ogden or Salt Lake City.

In the spring of 1860 the Gardners, Hancocks, Bakers, Woods and others located at Mendon. As new settlers began to arrive, it was evident that more irrigation water would have to be provided so it was decided to make a storage dam of the Gardner Creek about three miles south of the settlement. As the water from this dam affected quite a number and the growth of the town in population and wealth depended to a certain extent upon it, it was made a community project and half of the people worked one day and the other half the other, until the dam was completed. It was finished and the water turned in in ample time for irrigation. Just as they were about to use the water the dam gave way and all the storage water was lost. The settlers were most discouraged but they went to work again to make another dam. This time the dam was made strong enough to hold the water, but the grain did not receive irrigation water in time so there was a light crop.

The public school was conducted for just a short period each year and Amenzo W. Baker was the first teacher. The school was held in the log meeting house and desks were placed around the sides and slab benches were used for seats. Reading, writing, arithmetic, and spelling were the subjects taught, with slates and slate pencils for the writing equipment. After the school quarter was over, the teacher visited the families and collected his pay, which consisted of wheat, flour, and other products. Money was very scarce and it was mostly barter and exchange with the people.

In 1864, after five years of living in the Fort, it was considered safe to build and move on the city lots and break up the lines of log house fortifications. Some of the log houses in the fort were moved onto the lots and reconstructed and presented a better appearance. The plat of the first survey showed only nine blocks, but later surveys were made and extra blocks provided as the settlement increased in population. In the fort, the settlers being so close together were compelled to live almost as one large family and they could help each other more. Borrowing and lending of supplied and utensils was carried on to a great extent, and with the houses so close together it was convenient. Each family could not afford to have all the necessary equipment, supplies and household articles, so they exchanged and cooperated with each other. In other words, they had things in common and the life in the little fort made the ties of friendship and neighborly love much stronger. On the other hand, it was a good schooling for the settlers as it took considerable self–control and tact to always keep in harmony and prevent little differences.

Along with the other settlements of the Valley, Mendon did it’s share in sending ox teams and wagons to Omaha to help bring the poor emigrants, principally members of the L.D.S. Church, to Utah. In the spring of 1861, the settlement was asked to fit out four yoke of oxen, a wagon and teamster or “bull wacker” to go to Omaha to help bring some of the emigrants to Utah. Amenzo W. Baker was the teamster and he made the trip of more than 2000 miles, or a six month’s journey, and returned without loss of oxen. The next year eight yokes of oxen and two wagons were provided and Peter Larsen and Isaac Sorensen make the trip without loss of oxen. Ralph Forester and Jasper Lemon were sent in 1863 and 1864. In 1864 Joseph H. Richards made the trip with four yoke of oxen and one wagon. Charles Bird, Jacob Sorensen and Joseph Hancock took three teams and made the trip in 1866. In 1867 the railroad had been extended more than half way from Omaha, so the journeys were not so far. This year Tarragut Stumpf and Lars Larsen made the trip with Bradford Bird as night guard.

These journeys were by no means pleasant and were fitted out in a simple manner. A little bacon, some flour, a few peas for coffee, one pound of sugar and some butter and eggs, which soon spoiled, were provided. When Peter Larsen and Isaac Sorensen made the trip in 1862, they had to wait for eleven days on Ham’s Fork in Wyoming, before they could effect a safe ford.

In 1866, Mendon with other outlying settlements was ordered to provide for more settlers or move into the larger settlements for better protection, as it appeared the Indians were determined for war and revenge over their loss at Battle Creek, (Battle of Bear River) with General Patrick E. Conner and his soldiers. At a mass meeting the people decided that rather than move to larger settlements or give up part of their land and water rights to accommodate more settlers, they would construct a rock wall around the meeting house for protection. All went to work, some hauling rock and others clay and sand. A number of loop holes were provided in the walls so one could shoot from any angle. After three weeks, the work was discontinued as it was haying time. No more work was ever done on the rock wall as the Indian scare passed over and the danger of attacks lessened.

It was not long until considerable progress was made in the building of better houses. The rock houses were quite an advance in building over the dugouts and the log houses with dirt roofs and dirt floors. The first rock house was built in 1865 and was owned by Mr. Joseph Baker. Robert Crookston and Robert Murdock were the masons. Mr. Baker still occupies this house for his residence and it is in a good state of preservation. This year the foundation and walls for the rock meeting house were constructed and the next year the building was completed. Mr. Robert Crookston and Robert Murdock were also the masons for this and other rock buildings in Mendon.

At this time a number of public buildings in the county were constructed of rock. Of all these, the one at Mendon is the only building that stands today. It is used as an amusement hall. For the construction of this building Mr. George Baker was appointed as the general chairman and he had full charge of raising the funds and getting the building completed. It is now one of the landmarks of the Valley.

The marketing of products such as grain, eggs and poultry and other farm produce was quite a problem. Often these were marketed at a loss, as merchandise was so expensive as it had to be hauled by ox teams from Omaha. For the first years, it was necessary to haul grain and other farm products to Ogden and Salt Lake City for merchandise. One bushel of wheat would purchase less than two yards of factory (cloth). Other merchandise was in like proportions. Although the bushel of grain did not represent much cash, it certainly did represent plenty of hard labor. To produce it, the land had to be plowed and made ready. The grain was then sowed, later irrigated; then at harvest time cut with a cradle and bound by hand. A chaff-piler did the threshing after which the grain was cleaned by a fanning mill turned by hand. Due to droughts, pests, and other things, some years grain became scarce and to secure seed and breadstuff, it became necessary to travel as far as Salt Lake City and borrow grain. The interest was one peck on the bushel. Frequently the wheat was smutty and it was difficult to make good flour.

Subsequently, George Thurston built a small gristmill between Mendon and Wellsville at the dam–site on the Gardner Creek, and the settlers felt fortunate in having a mill so near where they could get their grists. While in the fort, peach trees were planted but they did not do well, so apple and plum trees were set out on the different town lots. For a number of years wild currants and strawberries were the principal fruits.

Later a temporary rise in prices for labor and farm products came to Mendon as well as to all parts of Cache Valley. It was at the completion of the Union Pacific System at the Promontory and the coming of the Utah Northern Rail Road to Cache Valley. Wheat sold for three to four dollars per bushel, and hay was hauled to the Blue Creek for from $40.00 to $60.00 a ton. A man with a team could earn from ten to fifteen dollars a day. The old adage, “come easy, go easy” became prevalent and the high wages paid and the good prices for the products were not saved and utilized as they should have been.

In the fall of 1866, the grasshoppers made their appearance and everywhere in the ground holes could be seen where the hoppers had deposited their eggs. The settlers were rather fearful about the crops for the next year, but all the land was sowed. Spring grain was the only kind sown in those days and the next spring when it had come up and was tender, the hoppers hatched and ate most of it off. As a result there was a poor crop but the settlers were able to get by because all the land had been sown. For several years the hoppers were a serious pest and the cause of much loss to the settlers.

A rather interesting economic and social order was established among the settlers of Mendon in 1874. Apostle Erastus Snow of the L.D.S. Church was sent to Cache Valley to introduce the Order of Enoch, or United Order, where all were to have things in common, so to speak. At a special meeting at Logan, the county seat, of all the settlements of the Valley, Apostle Snow presented the plan and workings of the Order. Acting Bishop (Ralph) Forester of Mendon reported that Mendon could not go into the Order until their bishop, Henry Hughes, returned from his mission. Apostle Snow very quickly and effectively asked the question— If the Kingdom of God had to stop in Mendon because Bishop Hughes was on a mission? This settled the question and an organization of the Order was at once effected in Mendon.

A president, two vice–presidents, a secretary and assistant, a treasurer and eleven directors were elected. All the real property of a member belonging to the Order was consecrated to the Order. This was done in good faith and the members never expected to own their property individually again. About one–third of the settlers joined the Order, while the other two–thirds remained out to see how well it would operate.

The members of the Order were organized into companies of ten with a superintendent over all. The men went to work together in the fields and just as soon as one piece of land was dry enough, it was plowed and sowed by the different companies. It was a rather novel sight to see the groups of men with their teams going to and coming from their work. Each member attended to the irrigating of the land he had turned over to the Order and he also kept and took care of his cows, horses, sheep and other livestock, for his family use. Each day’s work was credited and when the harvest was over and the threshing done, the net proceeds was determined and the amount allowed for each day’s labor was paid. The man with twenty-five acres of land fared no better than the one with five acres, or the one with none, unless he worked more days. They were paid according to the days they worked.

After a year or more, it was evident that the people were not ready for such a social and economic change, where selfishness had to be abolished and each have a desire to do his share and not impose on another. This was a real opportunity to cultivate the spirit of unity, loving one’s neighbors and having an interest in the welfare of the group along with one’s own. During the winter of 1875, most of the men in the Order worked in Providence Canyon, cut logs and hauled lumber to Ogden. The next fall the Order was discontinued and the lumber and cash on hand, as well as the net proceeds of the crops were divided among the members. Mendon gave this innovation a fair trial and was perhaps as successful with it as any of the other settlements.

A severe winter was experienced by the people in 1873-1874. It commenced in November and did not break up until the middle of April. Feed for livestock became so scarce that all the old straw on the sheds that had been there for several years was taken of and used for feed. As soon as there were bare places on the sunny side of the hills, the stock were driven to these to get what little dry and green grass they could. Much of the grain in the bins had to be fed to save as many of the stock as possible. Most every family had a few sheep and these became diseased and scabby. Much of the stock was on the lift and took some time for it to recuperate. The horses were so poor they could scarcely work at all and it was difficult to prepare the land and get the crops planted. If the dirt roof houses and dugouts had been in existence, many would have been tempted to rob them of the long grasses and straw under the dirt coverings.

A similar winter occurred in 1879 when the stock became so poor and weak that special groups of men had to go around and help lift the horses and cows to their feet so they could get around to help themselves. This was a hard winter on the grain bins and the cows produced very little milk. All the sheds were robbed of their straw for feed. Despite these hard winters every few years, the people were slow to accept the suggestions of President Brigham Young that in times of plenty they should save and conserve for times of scarcity. He advised the farmers to pile their straw around the chaff(–piler) from year to year and save it, but many when they had plenty would burn it to get it out of the way, whereas the practice of a little conservation would have saved much starvation and worry. To read of these severe winters reminds the present generation of the winter of 1917 when feed for livestock was so scarce that it sold for $40.00 to $50.00 per ton and much of the livestock was on the lift.

None of the smaller settlements of the Valley, such as Mendon, were incorporated at such an early date. This occurred in 1870 and was brought about principally because the settlers feared that with the coming of the railroad into the town, saloons and other public undesirable places might be established. With the settlement incorporated they could regulate such places to better advantage. Ordinances were at once passed which prohibited the sale of intoxicating liquors. No saloons were ever started in Mendon. Mr. George Baker was elected as the first Mayor.

Most all the early settlements had experiences with the wild game, some of which were unfortunate for the people. In the late fall of 1862, Mendon was shocked over the death of Father Graham, one of it’s settlers, by a large female grizzly bear and her cubs. Father (Thomas B.) Graham and Andrew P. Shumway were cutting willows on Muddy Creek, (Little Bear River) east of Mendon. They met the bear and her cubs suddenly and she attacked Father Graham, Mr. Shumway returned to Mendon at once and gave the alarm. Practically all the men armed themselves with guns and other weapons and went to Muddy Creek with all possible speed. Father Graham was already dead and his body mangled in a terrible condition. The men had quite an adventure before the bear was killed by a shot from the gun of James Hill. In one of the charges of the bear, Daniel Hill, in order to protect himself, rammed his gun down the bear’s throat. The two cubs were also captured.

The Indian troubles and more of the social and domestic conditions of Mendon will appear in a general account later. In conclusion, the writing of an historical record of Mendon from the beginning and recording the important events as they transpired in the settlement, Mr. Isaac Sorensen, one of the founders of Mendon, rendered a service to his community that some day will be appreciated perhaps more than he ever realized or imagined. His record is far more valuable that any diary because it is so much broader in it’s scope and does not deal in a personal way. All through the record Mr. Sorensen is very modest and here he refers to himself it is only indirectly. The people of Mendon owe him a debt of appreciation as he did something that was not done in any other settlement of the Valley. His ability for recording and describing events and his style impresses one. His record should be bound and preserved as one of the most valuable books of the settlement. Most of the information for the foregoing historical account was gathered from Mr. Sorensen’s record.

Following are the words of a song composed by Mr. Sorensen and which was sung for a number of years in the early days of Mendon. Mr. Sorensen, who took great interest in music and singing and possessed a sweet tenor voice which he trained while herding cows as a boy composed the music for this and other songs. He had much natural ability for music.

The Glorious Twenty-Fourth —

We hail the glorious twenty-fourth,

Its memory ever dear,

The day when first the pioneers

In Salt Lake did appear,

With Brigham Young their leader

Across the dreary plains,

They march with spirits eager

The valleys to obtain.

Chorus

We hail the glorious twenty-fourth

It’s memory ever dear,

The day when first the pioneers

In Salt Lake did appear.

They could no longer tarry

In lands of tyranny,

Where liberty and freedom

In every heart should be.

So out into the desert

They hurled this little band.

Triumphantly they shouted,

We’ve cleared them from our land.

And now behold our cities

In splendor and in fame.

Oh mob where is your pity

Your lot is endless shame.

You drove us from our dwellings

But yet with spirits gay,

We celebrate the memory

On this eventful day.

(Note: Since writing the historical sketch of Mendon, Mr. L. K. Wood has given the information that Heber C. Kimball named Mendon after his birthplace, Mendon, Ohio. This account is given in his biography.)