Indian Warfare at Battle Creek

The state of Idaho was settled permanently first at Franklin, Franklin County by a small band of pioneers and trail blazers in the spring of 1860. These people emigrated from the vicinity of Salt Lake City and other towns in that region because they had heard of the wonderful fertility of the soil in the well known Cache Valley. They selected a spot on the banks of Cub River and immediately began to build homes and prepare to remain permanently on their newly possessed farms.

At the time the state of Idaho was a vast wilderness known only to the hunter the trapper, the prospector and the Catholic missionary. Its vast wealth was not even dreamed of, its resources were wholly undeveloped. Franklin then was on the extreme outskirts of civilization. A thin line of settlements connected it with Salt Lake City, but that line was so puny that the smallest mistake in the treatment of the numerous and populous bands of Indians that roamed through the southwestern part of the territory might have snapped it and prevented the permanent settlement of the state for an indefinite period of time.

The pioneers, however, realized their precarious situation. They followed the policy that it was cheaper to feed than to fight the red men. This policy, though it prevented bloodshed for a time, led the Indians to believe that their word was supreme law. Since Cache Valley was used by several bands as a winter camping ground, their demands were often unreasonable and burdensome.

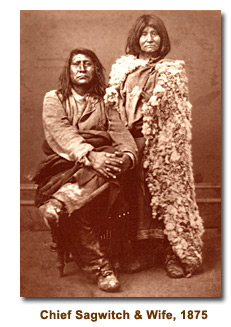

During the winter of 1862-1863 a large tribe of Indians, under the leadership of Chiefs Bear Hunter and Sagwitch, were encamped near the mouth of what is now Battle Creek on Bear River, about twelve miles north of Franklin. Indians selected that wintering place on account of the sheltering red clay bluffs which prevented the north wind from blowing upon their wigwams. The high clay banks and dense growths of willows that lined the little stream also offered opportunities for protection against the cold; and the subterranean hot wells of the region warmed the whole surface of the camping ground.

These Indians so out-numbered the whites that they felt they had only to ask and the pioneers would be compelled to give, consequently a food bin was maintained in Franklin to which the settlers contributed and from which the Indians drew when in need. Wheat was not the only commodity, however, that was contributed by the white men to their red brethren. The Indians, feeling immune from punishment, often augmented these forced gifts with cattle, chickens and other materials which they stole outright from settlers.

Conditions had grown so bad by mid-winter 1862 that the settlers in northern Cache Valley were becoming greatly alarmed. They felt that at any moment the Indians might sweep down upon them to drive them from their homes and kill many of them. As a result of this fear which all felt, the people had drawn in from outlying homes and were living most of the time in the fort which had been built at Franklin. Since the little log cabins which had been reared with much toil, represented the only homes they had, the outlook was anything but cheering to the little band of settlers. However, an incident occurred toward the close of the year which terminated in the almost total annihilation of the Indians who had become a menace by day and a terror by night.

In late December, David Savage, William Bevins and a company of men came down from the mines in the Salmon River country to procure supplies and cattle. Not knowing the fords across Bear River and being somewhat confused by a blinding snow storm, they followed down the west side of the river to a point somewhere west of Richmond, Utah. Here they stopped, made a ferry boat of wagon boxes and crossed over to the east side. As the last boat load was crossing the river, some Indians who had followed the travelers from Battle Creek, began shooting at them. One man was killed and several wounded. The white men hid in some brush near the river and waited for night-fall when they made their way to Richmond and reported the affair to the authorities of the town. The next morning, Bishop Marriner W. Merrill sent some men out to get the dead body and whatever property the Indians had not destroyed. This company was attacked by a strong band of Indians but succeeded in getting the body of the dead man and a number of horses. Savage and his companions were sent to Salt Lake City where the report of the actions of the Indians was given to the commandant at Fort Douglas and resulted in the expedition against the red men.

After the shooting of the white man, the Indians seized the property of the miners, cut their good wagons into bits, made whip stocks of the spokes of the wheels and showed a decidedly mean spirit generally.

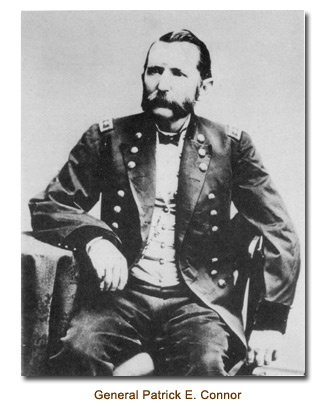

Colonel Patrick Edward Connor, upon hearing the report of the miners, fitted out an expedition for the purpose of punishing the Indians. In his report of the matter which was sent to Washington and which is on file in the War Department, he gives the following reasons for his actions: Colonel: “I have the honor to report to you that from information received from various sources of the encampment of a large body of Indians on Bear River, Utah Territory, 140 miles north of this point, who had murdered several miners during the winter passing to and from the settlements in this Valley to the Bear Head mines east of the Rocky Mountains, and being satisfied that they were part of the same band who had been murdering emigrants on the Overland Mail Route for the last fifteen years and the principal actors and leaders in the horrid massacres of the past summer, I determined although the season was unfavorable to an expedition in consequence of cold weather and deep snow, to chastise them if possible.”

Colonel Connor and his men came none too soon, for the Indians feeling sure that their numbers guaranteed their safety, levied tribute more determinedly than ever after the killing of the miners. On January 27th, Chief Bear Hunter and a party of warriors went into Franklin and demanded twelve, two-bushel sacks of flour. Upon being given that amount, they demanded more, whereupon the settlers refused and the Indians performed a war dance around Bishop Preston Thomas’s house, all the time flourishing their tomahawks and threatening the people. The following day, Bear Hunter in company with three young bucks, returned to the settlement for wheat. He secured two, two-bushel sacks of grain which the Indians took with them upon their horses and all was in readiness for their departure when Colonel Connor’s infantry was seen crossing over the rise south of town. The old chief did not seem alarmed but waited for their approach. As the soldiers drew near to the settlement, the old chief dismounted from his horse and began mimicking the march of the soldiers.

“Two’s right, two’s left,” he would cry, “Come on you blue coated sons of bitches.” As the soldiers drew nearer and nearer, the old chief mounted his horse and prepared to leave. Someone remarked, “The soldiers are getting pretty close, perhaps you will get killed.” “May-be-so soldiers get killed too,” he replied as he rode away into the north, followed by the two Indians. The old fellow must have been a little more afraid, however, that he pretended to be, as his sacks of wheat were found by the way-side just north of town. It was evident that he thought it unnecessary to carry excess baggage.

In the meantime the infantry marched into Franklin and found lodgment in as good quarters as the settlers could furnish. Colonel Connor had arranged his expedition in two detachments, the infantry and howitzers, which led, and the cavalry which brought up the rear. He did this in order that the Indians might not guess his strength and escape. His scheme worked well as Bear Hunter saw only the infantry and felt that he could withstand successfully their assaults. The cavalry did not reach Franklin until sometime in the night.

All this time this march was taken, the weather was extremely cold. The snow lay deep upon the ground and the thermometer registered below zero most of the time. The loud creaking of the army wagons as they lumbered through Cache Valley towns on their way to the battle ground is still a vivid recollection in the minds of some of the older inhabitants.

When Colonel Connor reached Franklin with the cavalry, he ordered the infantry to move on at one o’clock. About one hour later the cavalry mounted and rode out in the wake of the slower infantry. Being able to travel much faster than the infantry and artillery, the Colonel passed the vanguard somewhere near where Preston now stands, hastened on to Bear River, which he reached just at dawn. The Indian Camp lay northwest from the ford about one mile distant. Colonel Connor fearing that the Indians might escape, ordered Major McGarry to surround the camp with the cavalry. Since the Colonel gives a very vivid description of the engagement in his report to Washington, we give here his exact story of the battle. He remained behind a short time to give orders to the infantry and artillery as it came up. He says:

“On my arrival on the field, I found that Major McGarry had dismounted the cavalry and engaged with the Indians who sallied out of their hiding paces on foot and on horseback and, with fiendish malignity, waved the scalps of white women and challenged the troops to battle and at the same time attacked them. Finding it impossible to surround them in consequence of the nature of the ground, he accepted their challenge.”

“The position of the Indians was one of strong natural defenses and almost inaccessible to the troops, being in a deep ravine from six to twelve feet deep and from thirty to forty feet wide, and with abrupt banks and running across the level table lands along which they had constructed steps from which they could deliver their fire without being themselves exposed. Under the embankments they had constructed artificial covers of willows, thickly woven together from behind which they could fire without being observed. After being engaged about twenty minutes, I found that it was impossible to dislodge them without great sacrifice of life. I accordingly ordered Major McGarry, with about twenty men, to turn their left flank which was in the ravine where it entered the mountains. Shortly afterwards Captain Hoyt reached the ford three-quarters of a mile distant but found it impossible to cross foot-men. Some of them tried it, however rushing into the river but finding it deep and rapid, retired. I immediately ordered a detachment of cavalry with lead horses to cross the infantry, which was done accordingly, and upon their arrival upon the field, I ordered them to the support of Major McGarry’s flanking party who shortly afterward succeeded in turning the enemies flank. Up to this point, in consequence of being exposed on a level and open plain while the Indians were under cover they had every advantage of us, fighting with the ferocity of demons. My men fell fast and thick around me, but after flanking them we had the advantage and made good use of it. I ordered the flanking party to advance down the ravine upon either side, which gave us the advantage of an invalidating fire and caused some of the Indians to give way and run toward the north end of the ravine. At this point I had a company stationed who shot them as they ran out. I also ordered a detachment of cavalry across the ravine to cut off the retreat of any fugitives who might escape, the company at the mouth of the ravine. But few tried to escape, however, but continued fighting with unyielding obstinacy, frequently engaging until killed in their hiding places hand to hand with the troops. The most of those who did escape from the ravine were afterwards shot in attempting to swim the river or killed while desperately fighting under cover of the dense willow thicket which lined the river banks. To give you an idea of the desperate character of the fight, you are respectfully referred to the list of the killed and wounded transmitted herewith. The fight commenced about six o’clock in the morning and continued until ten a.m.”

“At the commencement of the battle the hands of some of the men were so numbed with cold that it was with difficulty they could load their pieces. Their suffering during this march was awful beyond description, but they steadily continued on without regard to cold, hunger or thirst, not a murmur escaping them to indicate their sensibilities to pain or fatigue. Their uncomplaining endurance during their four night’s march from Camp Douglas to the battlefield is worthy of the highest praise. The weather was intensely cold and not less than seventy-five men had their feet frozen and some of them, I fear, will be crippled for life.”

After praising his men for their excellent conduct, Colonel Connor says:

“We found 224 bodies on the field, among which were those of Chiefs Bear Hunter, Sagwitch, and Leight. How many more were killed than stated, I am unable to say as the condition of the wounded rendered their immediate removal a necessity. I was unable to examine the field. I captured 175 horses, some arms and destroyed over seventy lodges, a large quantity of wheat and other provisions which had been furnished them by the Mormons. I left a quantity of wheat for the sustenance of 160 captive squaws and children whom I left of the field. The Chiefs Pocatello and San Pitch, with their band of murderers are still at large. I hope to be able to capture them before spring. If I succeed, the Overland Route west of the Rocky Mountains will be rid of the Bedouins who have harassed emigrants on the route for a series of years.”

As was stated by Colonel Connor the intense cold and the conditions of the wounded rendered an immediate move from the field imperative. Many of the settlers furnished teams and wagons or sleighs with which to haul the wounded and dead from the field. These were taken back to Franklin where the settlers did all in their power to relieve the suffering of the living and make them comfortable. Good, clean straw was put was put in the meeting house, and beds were made upon it for the wounded. Several of the settlers went to Salt Lake along with the command to assist in hauling the dead and the wounded, who could travel, back to Salt Lake City.

Many of the pioneers who lived in Franklin at that time and who opened their homes to the soldiers, declare that they did it freely and without charge as they felt they had been rendered a great service by the soldiers.

There is quite a discrepancy between the number of Indians reported killed by Colonel Connor and the number of dead Indians actually counted by men who live in Franklin County today, but the difference may be accounted for when we consider the Colonel’s haste to get his wounded men to shelter. In his report, Colonel Connor reports 224 dead Indians, but that the number was very much greater is certain. The Colonel also reported that 160 squaws and children were taken captive, whereas a number of living pioneers declare that the number of living souls who came through the bloody fight was very small. It must be remembered that the women fought as desperately as the men and all fought like tigers. It is reported that a young drummer boy fell wounded and that while lying upon the snow two Indian lads, mere infants, ran out with their case knives and attempted to cut his throat and might have succeeded had their efforts not been stopped by the Colonel himself. Three Indian babies and two squaws wee taken to Franklin where they were cared for by the kind hearted people. One of these was reared to manhood by Samuel R. Prakinson. He was known as Shem Prakinson and died when he was nearly twenty-five years old. A girl was taken into the home of William Hull where she was reared carefully under the name of Hull. Later in life she married and reared a respected family, dying but recently, loved by many people. There were the only two of the children that survived until they were grown.

Colonel Connor was mistaken too when he reported that Chief Sagwitch was among the killed. Some of the pioneers declare that the cunning old chief was not present and escaped. Whichever version is correct, it is certain that he was not killed on that day as he was shot many years later near Brigham City, Utah. The son of Chief Sagwitch was in the battle and escaped in a very daring fashion. He ran toward the river during the engagement with several soldiers in hot pursuit. Upon reaching the bank he fell into the water as though dead, while the soldiers volley whistled harmlessly over head. He floated under the ice and made for an air hole where he clung with his head just out of the water enough to allow him to breath freely. While in this position, the soldiers sighted him and fired upon him. He withdrew momentarily from the opening, receiving only a wounded thumb. The soldiers returned to the battlefield and the courageous young fellow swam to a bunch of willows, where he lay hidden for several hours in the intense cold. How he ever escaped being frozen is a wonder. This man was interviewed at his home in Washakie, a few years ago, by S. P. Morgan. He told Mr. Morgan that twenty-two young bucks made their escape in various ways from the vigilant Connor. He also stated that the Indians had planned to raid the white settlements as soon as spring should open up.

Bear Hunter, the leading chief and as villainous an old fox as ever wore buckskin, was found dead by his fire. Evidences pointed to the fact that he had been engaged in molding bullets when death came.

The battle was a very important on to this state as it marked the close of the real Indian troubles of this section of the territory. The Indians were taught a lesson that remained with them for many years. While it seems cruel to us when we look back upon the affair, yet we must remember that those were the days of the primitive— the fittest survives.